1 What is Computer?

1.1 The General View

Therefore, what is a computer? There may be many different answers depending on the person asked. I would say that a computer is a type of machine that can be programmed to perform tasks automatically.

Early computers were primarily designed for numerical computation tasks such as calculating ballistic trajectories. By contrast, modern computers can perform a wide variety of general-purpose tasks. If early computers behaved like pure calculators, I would describe modern computers as automatic executors of algorithms.

This shift from specialized number crunching to versatile programmability marks the essence of the computer revolution. It is not only about speed but also about flexibility — the same machine can run entirely different programs, from scientific simulations to web browsing or gaming.

1.2 The Abstract View

1.2.1 The Software/Hardware Interface

We can also view computers as a type of machine whose mission is to execute the desired software.

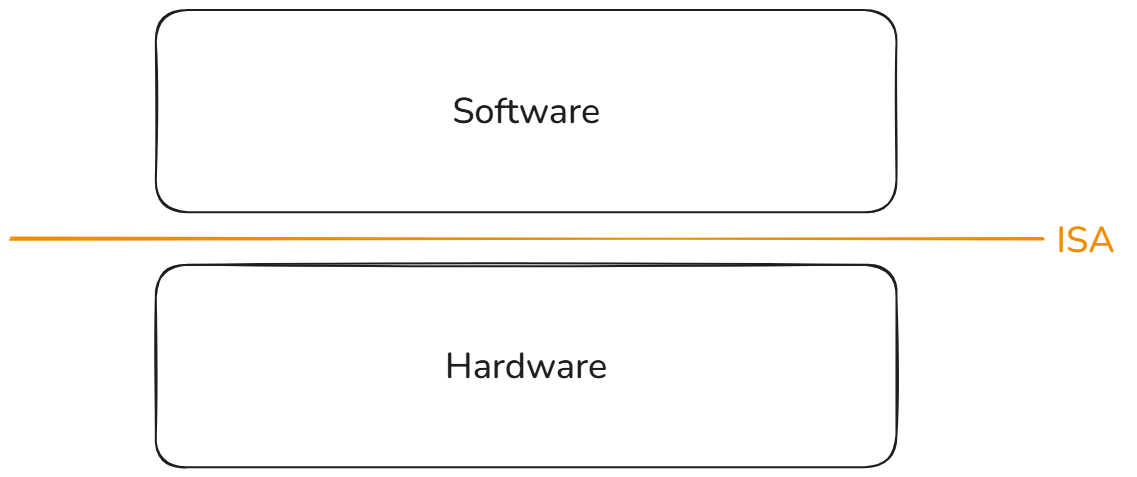

One big question is that how does a computer interpret or execute different programs? Computers are only a set of transistors, and how can they execute programs? The key idea is the Instruction Set Architecture or ISA. The ISA is a type of abstraction (indirection) layer. ISA can be viewed as a common language between software programs and hardware implementations. Furthermore, ISA also decouples the details of the software and hardware.

In general, computers are often referred to as the hardware in the figure above. A computer is a kind of hardware implementation which can recognize one or more kinds of ISA. With the power of ISA, the computer (hardware) can execute different programs and complete specific tasks.

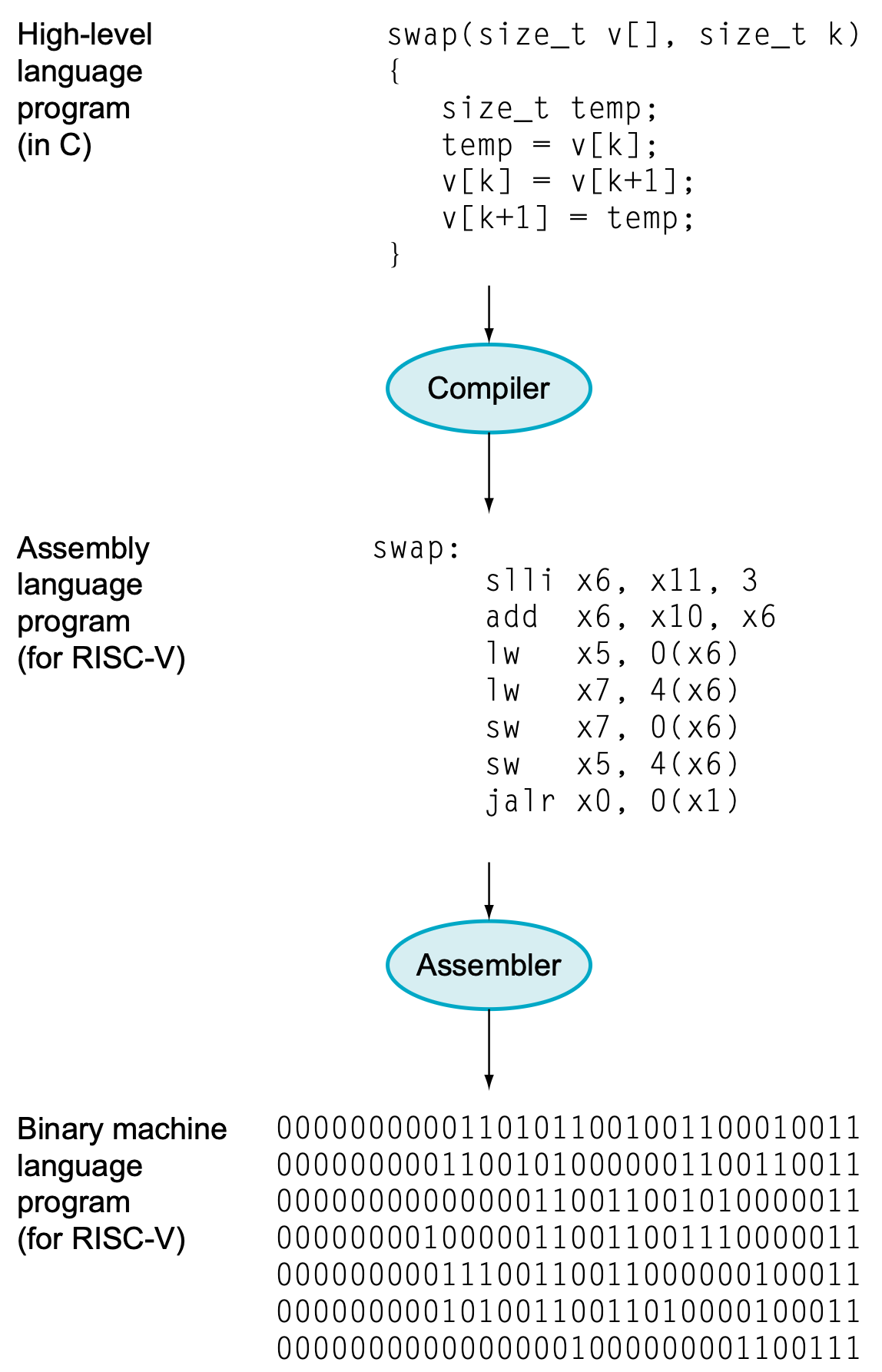

The programs we write must first be translated into instructions defined by a specific ISA. However, processors can only understand binary representations—sequences of 0s and 1s. Therefore, assembly instructions must ultimately be converted into machine code, which is the actual binary encoding executed by the processor. Please note that the binaray represenation of each instruction are also defined by ISA.

In summary, an ISA can be regarded as a formal specification that defines:

- The instruction set and its encoding formats

- The execution semantics of each instruction

- Additional rules governing program behavior (e.g., traps, exceptions, memory model)

1.2.2 A Sophisticated Finite-State Machine (FSM)

From another perspective, a computer can be viewed as a large and complex finite-state machine (FSM). From this perspective, the two most important questions are as follows:

- What is the current state of computers?

- How does a state transition occur within a computer?

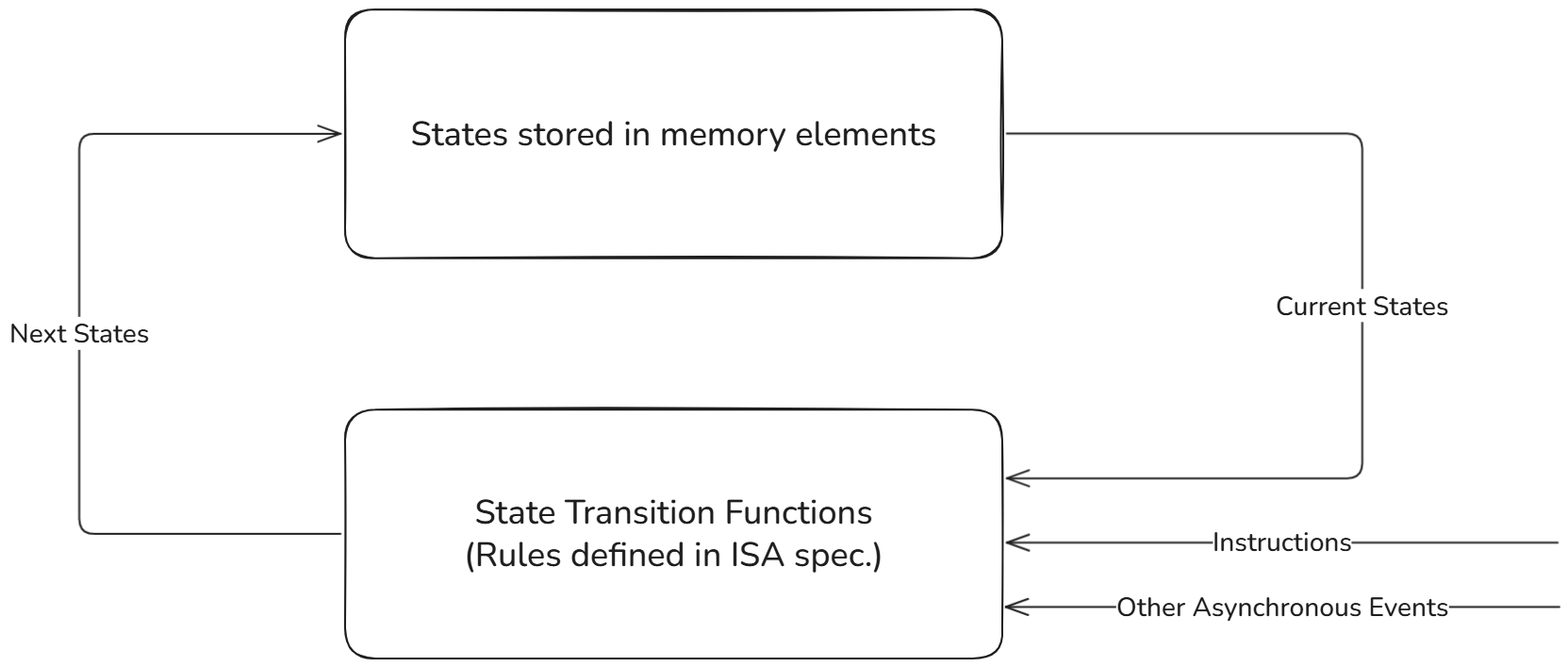

By definition, the state of an FSM are stored in memory elements. In a computer, these memory elements are the processor registers and memory devices (units).

The state transition function for a processor implementing specific ISA is rules defined in the ISA specification. The term rule here is broad: it includes not only the semantics of individual instructions but also any other definitions provided in the ISA specification that govern state transitions.

You may also notice a special trigger event in the figure above, labeled other asynchronous events. These refer to the traps in the RISC-V ISA, such as exceptions (synchronous) or interrupts (asynchronous). Although traps are crucial for real processors, they will not be covered in this lab.

This FSM perspective also explains why an Instruction Set Simulator (ISS) only updates the architectural state during the Execute stage—it is simply applying the next-state transition function defined by the ISA.

In the narrow sense, a finite-state machine (FSM) usually refers to a very simple model you may have seen in textbooks: it has a small number of states (e.g., S0, S1, S2) and transitions defined by a few simple rules. These FSMs are easy to draw on paper and are often used to describe control logic.

In the broad sense, a computer itself can also be described as a finite-state machine. The difference is that the “state” here is enormous — it includes the contents of all registers and memory. In theory, we can still view the computer as an FSM, while its state space is too large to be drawn as a simple state diagram.

So, when we say “a computer is a finite-state machine,” we mean it in the broad theoretical sense. We are not implying that it looks like the small FSM diagrams you have seen before, but the underlying principle—state + transition rules—still applies.

1.3 The Detailed View

1.3.1 Von-Neumann Architecture

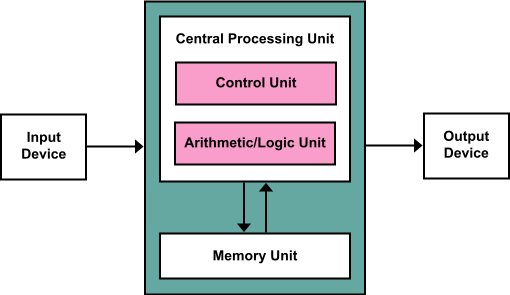

One type of computer organization is known as the Von-Neumann Architecture, which was first discussed in the well-known report on the early computer EDVAC [2]. The fundamental idea of this architecture is to divide the computer system into five major components: the central arithmetic unit, the central control unit, the memory, and the input/output devices.

A key feature of the Von Neumann Architecture is the unification of data and instruction memory. In other words, both program instructions and data are stored in the same memory unit, and they share the same communication pathways. This design greatly simplified early computer construction and programming, but it also introduced the so-called Von-Neumann bottleneck, where the shared memory bus can become a performance limitation.

In order to execute a program, the computer must read instructions from the unified memory, and the control unit (C.U.) will try to recognize what the instruction is. After decoding the instruction, the C.U. will try to control the arithmetic unit (A.U.) to perform specific operations and gives the calculation result.

For a more general program, it is often that the program needs some input from the user and gives the output to the user/programmer. Hence, the input/output units are also necessary parts.

1.3.2 Harvard Architecture

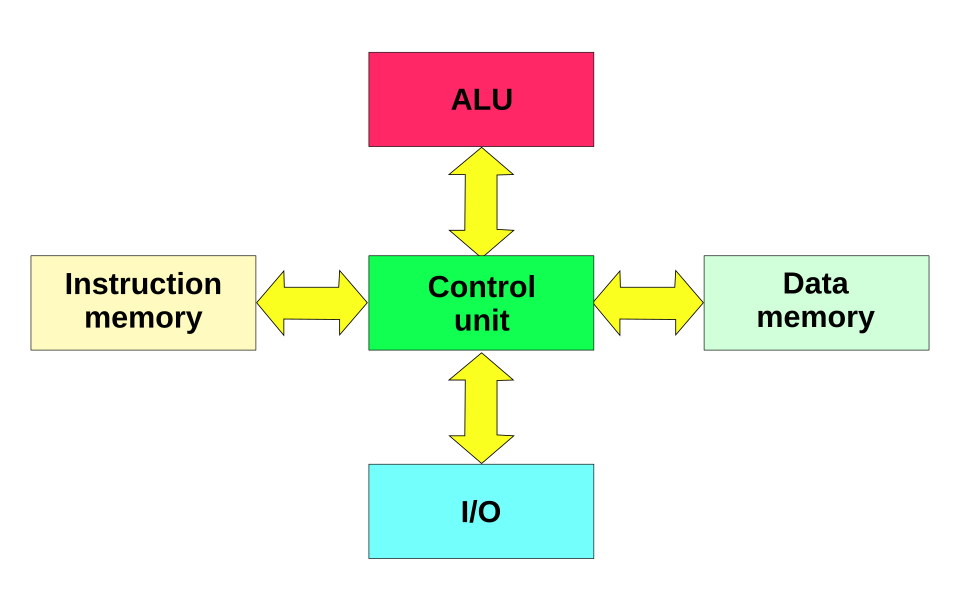

Harvard Architecture is firstly introduced in the early mainframe called Harvard Mark I.

The main difference between Von-Neumann Architecture and Harvard Architecture is that the specification of memory unit. With Harvard Architecture, the Von-Neumann Bottleneck can be solved with separated data and instruction bus, while the hardware cost increases.

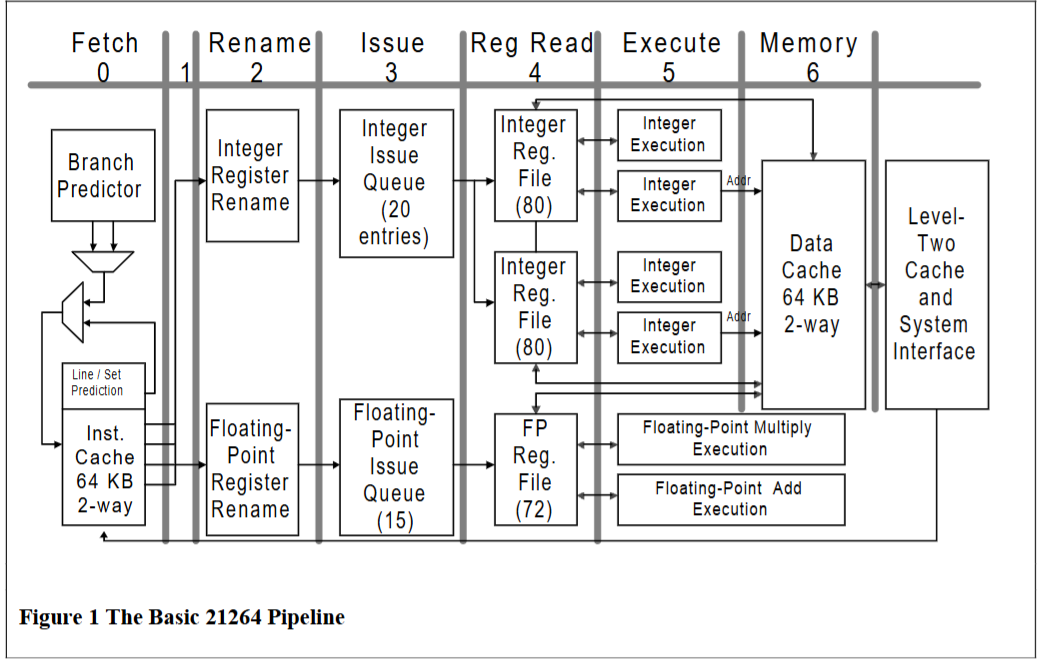

In modern processors, you can find that the processor itself is hard to be defined as exact one kind of architectures among Von-Neumann and Harvard. The modern processors are often hybrid architecture.

Such as the microprocessor above, it has separated instruction and data memories, which is Harvard Architecture. However, it also has a unified memory as the next-level memory for first-level instruction memory and data memory. The scheme of the unified memory is like Von-Nuemann Architecture.

1.4 Memory Map

What is the essence of memory?

1.4.1 Physical Memory Space

For a 32-bit processor, the addressable memory range spans from 0x0000_0000 to 0xFFFF_FFFF. We usually refer to this range as the physical memory space, or simply memory space.

In practice, however, low-end systems often have only a small amount of actual readable memory (such as RAM or Flash), sometimes as little as 64 KiB. This leaves a large portion of the memory space unused. Instead of wasting it, the unused address regions can be mapped to other purposes.

1.4.2 Generic Memory Devices

What is a memory device?

In a narrow sense, a memory device is simply a circuit that contains memory elements to hold values.

In a broader sense, however, we can generalize the term to mean any device that can be accessed through load and store operations. In this view, a generic memory device is characterized by a base memory address, a memory range, and load/store interfaces.

From the processor’s perspective, such a device can be manipulated using standard load/store instructions, in the same way it interacts with ordinary main memory.

1.4.3 Memory-Mapped Device (Memory-Mapped I/O, MMIO)

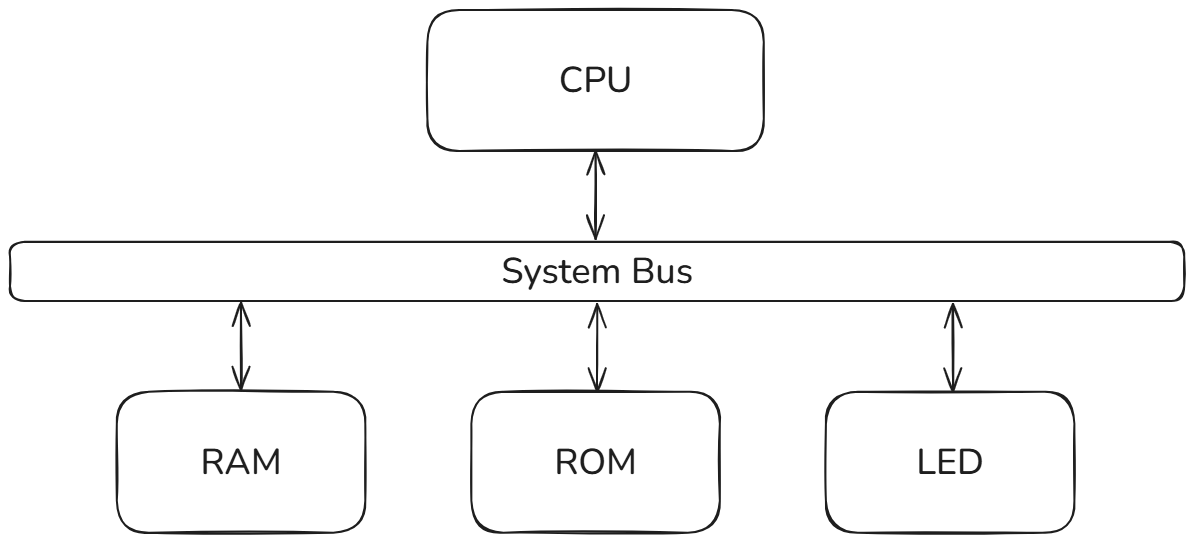

At this point, we already understand what a computer is and how it operates internally. However, a big question remains: how do the different components inside a computer communicate with each other? To explore this, let’s consider a very simple embedded system, as shown below.

How can the CPU control LED lights? One straightforward approach is to treat the LED as a type of memory-mapped device. Suppose the LED is assigned a base memory address of 0x200, with a memory range of 4 bytes. Inside this device, there is a control register that can hold either the value 0 or 1.

- When the control register holds 1, the LED turns on.

- When it holds 0, the LED turns off.

For the processor, it can turn on the LED light by using the following instructions:

Likewise, the processor can turn off the LED through the instruction below:

Now, suppose that we want the processor to automatically turn off the LED whenever it is on. A simple program may look like this:

Why does not processors use extra instructions to control LED lights? What is the benifit for using MMIO to control LED lights?